Success in the vast marketplace of natural health products is no easy feat. Where does one begin? Well, you could find a unique ingredient in the wild with some as of yet unknown medicinal properties. However, you would need to identify the valuable ingredient, demonstrate a potential medical use, ensure safety in effective doses, run clinical trials, register with Health Canada, and finally figure out bulk production. I’ll be honest with you, I’m not about to go to the trouble.

So why not take a few shortcuts? Why not identify an existing ingredient that already has Health Canada approval and then simply re-appropriate the ingredient for a similar, but distinct medicinal use? Give it fancy branding and position it as a unique product within the marketplace, permitting significant mark up. Without the serious science, the product will need something to lend legitimacy; maybe association with a major research institution or university? Bingo.

Entirely unrelated to the above hypothetical, I recently came across an article by Global News published earlier this month promoting a new “Hangover Pill” created in Manitoba. I immediately rejoiced; as documented by the World Health Organization, hangovers are the leading cause of death in the developed world and the second leading cause of getting up late on Sundays. What’s worse, there is no known preventative measure; it could happen to anyone at any moment. Just kidding, that’s bullshit. So, too, is the article.

The article describes a hangover remedy called Clear Head. If you’ve been drinking and that’s too difficult a name to remember, don’t worry; the article names the product a whopping 7 times. Read on and you will get it eventually. What you won’t get is any serious science or skepticism.

The article claims that “Clear Head works to counteract the action of [brain receptors]” and also “helps the liver clear the toxins.” Ah, of course! It’s those pesky toxins again. The product’s origin story is even more dubious.

Alex began researching vitamins and ingredients he thought might help with his dreaded hangovers.

“I compiled a list of products I thought would help me,” he said. “I started to divide and conquer these ingredients by experimenting on myself and friends to better understand what is the actual ‘magic’ ingredient.”

Well, that sounds both scientific and ethical. Luckily, Alex realized that experiments on his buddies might not be the most valuable in developing a health product, so he passed the torch to his father Ron Marquardt – a professor at the University of Manitoba. The team also enlisted the help of marketing specialist and distributor Ray Takacs, who is careful to only make reasonable scientific claims when promoting the product.

If you use it properly, it will work.

Ray Takacs, T.H.E Food Source Owner and Clear Head distributor

Oh, never mind. Well with that confidence, there must be some high-quality evidence supporting this product. Let’s start with what we know from the original promoter – ah hem – I mean reporter. What evidence is reported?

“Clear Head was developed at the University of Manitoba and has a Health Canada stamp of approval.”

None, of course, but why bother with science when we can invoke scientific authorities? But wait; are these legitimate scientific authorities?

Let’s start with Health Canada. As I’ve noted in the past, Health Canada – despite their claim otherwise – does not require a product to demonstrate efficacy prior to registration as a natural health product. In place of legitimate evidence, Health Canada permits “traditional use claims,” meaning if someone has used some natural product in the past for anything and sufficiently documented it, the text – scientific or not – can be used in place of sound evidence (with minor restrictions). If anyone from Health Canada is reading, I want you to know that you are doing a bad job and should feel bad.

I’m sure you know where this is going: Clear Head’s registration with Health Canada relies not on well-designed clinical research, but on traditional use claims referencing monographs that existed long before the product. Although the main ingredient – silybum marianum (milk thistle extract) – has been examined as a potential “liver protectant,” it has failed to pass the rigor demanded of clinical trials.

A 2007 Cochrane review noted that there is no reliable evidence supporting its use. Higher quality evidence tended towards negative results, which is expected in the absence of a real effect. A 2012 randomized controlled trial (RCT) did not show any liver benefits for subjects with hepatitis C. Oh, and a 2017 systematic review of biochemical indicators of silymarin effects in patients with liver disease concluded results were “without clinical relevance.” Worse still, not a single RCT has been published on silybum for hangovers. Even Health Canada’s monograph does not mention hangovers once. Oops!

Perhaps the reporter should have looked this information up before publishing a suggested dose:

Each packet comes with four capsules. People take two before consuming alcohol and then one more before they go to bed. The fourth is a spare, to take the next morning if you need it.

Then again, can we blame her when a CBC reporter failed the same critical thinking step before reporting nearly identically two years earlier (2016):

Each packet comes with four capsules and you’ll need to take two before consuming alcohol and then one more at the end of the evening. The fourth is a spare, in case you need it the next morning.

A simple perusal of the product’s website should be enough to sense that straws are being grasped at to legitimize the product; the site offers a single testimonial and a “Why It Works” page that provides no evidence supporting the claim that this hangover cure “actually works.” Can you spot the appeals to nature and tradition?

All natural ingredients

Clear Head is prepared from an extract of Silybummarianum [sic] (Milk Thistle). The active compound in the extract is silymarin. This extract has been used for over 2000 years to treat a range of liver diseases. More recently, it has been shown to be effective in the relief of symptoms of hangovers.

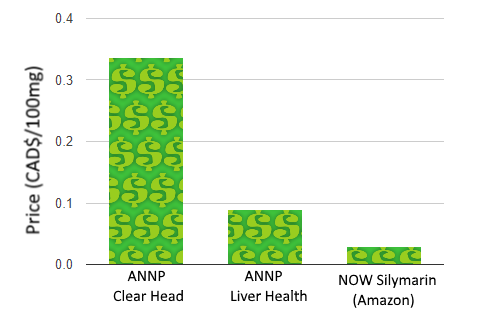

A look at the ANNP’s website also reveals that the ingredient is not novel. While you can pick up 12 pills of ANNP’s Clear Head for $10, they also offer a silybum product without the Clear Head branding at $21.16 for 90 pills. If you’re not convinced the products are identical, Health Canada includes both under the same registration initially licensed in 2010.

Of course, you can also find silymarin much cheaper on Amazon, but perhaps lacking the backing of a research institution.

If we were to base our purchase on the product making the most grandiose and unsubstantiated health claims, however, ANNP’s Liver Health steals the show:

While none of these claims are supported by high-quality evidence, there is something more troubling here: these are unambiguous schedule A disease prevention claims in the context of product marketing. While Health Canada permits direct-to-consumer prevention claims for natural health products, the claims must first be authorized. As none of these claims are supported by the product’s registration, why exactly would Health Canada permit them?

When it comes to the product’s relationship with the University of Manitoba (UM), the story gets more complicated. You would think the connection is straight forward considering Clear Head’s Facebook page proclaims that Clear Head was “Created at the University of Manitoba!” ANNP has even deemed the relationship important enough to place on marketing material.

What’s up with that? Well, UM is home to the Richardson Centre for Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals (RCFFN) – a “bioprocessing and product development facility” whose mission is to “lead functional food and nutraceutical research for the improvement of health and nutrition” and “support the development of an economically viable functional food industry.” The RCFFN hosts the aforementioned ANNP, who developed the Clear Head product. Just as in their ad, the Clear Head website prominently brandishes this connection:

Developed at the Richardson Centre for Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals at the University of Manitoba.

Yet the RCFFN merely leases space and equipment, prominently indicating on their website that ANNP is a tenant. To say the product is developed at the University of Manitoba is true geographically, but the product is not developed or endorsed by the University of Manitoba. In fact, there is no indication that any clinical research on the product has been performed at the university. It is, however, developed by professors at the university.

Heading up the ANNP is the aforementioned professor, Ronald Marquardt – ANNP president, UM professor, and Clear Head “developer.” Dr. Peter Jones – a scientific and business adviser with ANNP – is the Director of the RCFFN at UM. I was unable to find publications by either professor on hangovers or silymarin. I reached out to the RCFFN, ANNP, and the professors. Vice President and R&D Director of ANNP, Dr. Suzhen Li, got back to me.

Regarding the evidence for Clear Head, Dr. Li directed me to Google Scholar, noting that there is “a very large number of scientific publications on silymarin dealing with the safety, efficacy, mode of action, etc.” She went on to list the number of publications containing relevant keywords in the title: “milk thistle” (944) and “silymarin” (2880). There are no publications that include both “silymarin” and “hangover” in the title, but Dr. Li noted that 568 publications contain both keywords in the text.

The large number of results indicates that there has been interest in the area, but it has no bearing on whether these compounds are valuable for anything. For example, the same search for “homeopathy” returns 5,280 results, yet we know that homeopathy is an implausible concept. In addition to quantity, we must consider the precise question that each study addresses and how rigorously the question is addressed.

In addition to highlighting the quantity of results from various search queries, Dr. Li provided the results from some, claiming that they “demonstrate that silymarin has many different beneficial effects in humans and animals.” Still, none of the studies are clinical trials examining silymarin and hangovers. I address each study in the Appendix.

While milk thistle and silymarin do appear to possess some interesting properties and biochemical interactions, the failure of the literature is in making the transition from the basic sciences to the clinical sciences. The distinction is quite important, but too often ignored in the pursuit of promising therapies. In essence, basic science involves research looking at the low-level mechanisms, often in a laboratory setting. For example, if we were looking for a novel compound to eradicate cancer cells, we might first test the compound in vitro on cells in a petri dish. Unfortunately, the success of such an experiment tells us very little about clinical applications.

Let’s suppose – for example – that we were examining bleach as a potential chemotherapy. While bleach would undoubtedly kill cancer cells in our petri dish, there remain unanswered questions required to make the leap to clinical applications. What is the toxicity of the compound and what are the side effects? How is it best administered? What is the optimal dose? What is the bioavailability? Does it make a meaningful clinical impact? Does it work generally at a population level or only under specific conditions?

In the case of bleach, we know that it does not satisfy these criteria as a cancer treatment. With novel compounds, there is an additional risk: there is a good chance that our knowledge of the basic science is incomplete. A popular example reader’s should be familiar with is the hype behind anti-oxidant supplementation. While our initial conceptualization of cellular metabolism demonized reactive oxygen species, contemporary research indicates that excessive anti-oxidant supplementation is not necessarily a good thing. As with most biological processes, the human body is often capable of maintaining a balance from a healthy diet alone.

For these reasons, I find the confidence of marketing claims for silymarin troubling. As in the Global News article, Dr. Li noted that “milk thistle’s ability to mitigate hangover was discovered by Alex Marquardt” and has been “confirmed by positive feedback response from many different users and by researchers,” yet this is not actual confirmation from RCTs.

If you are not yet scientifically triggered, look at how ANNP represents Health Canada licensing on their website:

In Canada all nutraceutical products must be licensed and issued a Natural Product Number (NPN). Products that are licensed have been shown to be safe (minimum of two clinical trials with humans) and effective (minimum of two clinical trials). Some companies market nutraceutical products that are not approved by Health Canada and often do not have the recommended concentration of active compound. Products that do not have a Health Canada NPN should not be purchased.

Based on this claim, would you not expect that products you buy from ANNP have been validated by two clinical trials demonstrating efficacy? At very least, should there not be a single, high-quality, double-blinded, and randomized study showing that individuals taking silymarin reported less severe hangover symptoms compared to those taking a placebo? Dr. Li responded to my concerns regarding their representation of Health Canada licensing:

This is a stated requirement by Health Canada and repeated by ANNP. Please consult the Health Canada milk thistle monograph to see if this is correct and, if not, please contact Health Canada to determine why they have issued an NPN for milk thistle to many companies containing 80% silymarin. We believe that some traditional medicine such as milk thistle can be issued NPN’s without safety and efficacy trials if they have been successfully used as a traditional medicine. You need to discuss this with Health Canada.

Dr. Suzhen Li, ANNP Vice President

Indeed, Health Canada’s registration notes traditional use claims. Again, this is a failure of Health Canada to properly require evidence of efficacy, but that’s no excuse to represent the product as proven effective. Regarding ANNP’s claims marketing their Liver Health product (such as “Cancer Prevention“), these claims were authorized by Nelson Pereira of Health Canada’s Inspectorate Program. I reached out to Health Canada and Nelson Pereira for comment, but have not yet heard back. I’m very interested to hear about the evidence Health Canada relies on to authorize these claims. After all, if milk thistle really could prevent cancer, wouldn’t we all want to be taking it?

In addition to the citations provided in the Appendix, Dr. Li provided me with a brief document outlining the basic research behind hangovers and the potential role of silymarin. While some of the research was interesting, there was still no clinical research in humans examining the benefits of silymarin for clinical endpoints related to hangovers.

Despite the lack of evidence demonstrating the product to be effective, ANNP has pushed forward, partnering with distributor T.H.E Food Source, and marketing the product to credulous reporters, radio shows, and “natural health” stores. They have even begun looking for Chinese distributors.

In all this marketing madness and curative certainty, only one limitation of Clear Head is offered:

If you go out and challenge it . . . you’re going to hurt.

Ray Takacs, T.H.E Food Source Owner and Clear Head distributor

So just don’t drink too much or it won’t work. This isn’t the first “hangover cure” that isn’t supported by clinical evidence and I doubt it will be the last. Bad journalism, bad marketing, bad regulation, and bad science are the status quo. As always, don’t buy the hype.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Terry Polevoy for bringing this issue to my attention.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Appendix: Selection of Milk Thistle and Silymarin Studies

The following studies were sent to me by ANNP. I provide a brief summary below each. None of them examined clinical efficacy of silymarin for hangovers. Overall, my impression was that the totality of the evidence simply does not support the hypothesis that milk thistle supplementation provides any meaningful benefits. A number of sources note that oral supplementation results in poor bioavailability. Additionally, although milk thistle is well tolerated at typical doses, side effects do occur, often in the form of gastrointestinal distress. Allergies may also be somewhat common.

Perhaps most telling is that US-based NCCIH (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health) – the NIH’s most infamous center – admits that “we know little about whether milk thistle is effective in people, as only a few well-designed clinical studies have been conducted.”

(Note: papers that appeared in multiple search results were only included in the first seen query section).

Search query: “allintitle: milk thistle saftey”

- Review of clinical trials evaluating safety and efficacy of milk thistle (Silybum marianum [L.] Gaertn.). (2007)

- This was published in a low-quality journal “Integrative Cancer Therapies” and even they concluded: “The future of milk thistle research is promising, and high-quality randomized clinical trials on milk thistle versus placebo may be needed to further demonstrate the safety and efficacy of this herb.“

- The Many Faces of Silybum marianum (Milk Thistle): Part 2 – Clinical Uses, Safety, and Types of Preparations. (2004)

- Another low-quality journal “Alternative and Complementary Therapies,” this is simply a narrative review written by an herbalist and naturopath. In their conclusion they reveal both their scientific ignorance and the lack of evidence: “Second, given the safety profile of the herb, clinicians would be well-advised to expand their use of this plant although clinical studies are lacking.” Just because something is relatively safe, does not mean it should be used clinically. Then again, that’s an apt summary of the naturopathic profession.

- Milk thistle in Wilson’s disease: what is the pledge of safety? (2015)

- This paper simply noted that products prepared with milk thistle could include significant amounts of copper, which should be avoided by patients with Wilson’s disease.

Search query: “allintitle: milk thistle review”

- A review of the bioavailability and clinical efficacy of milk thistle phytosome: a silybin-phosphatidylcholine complex (Siliphos). (2005)

- This review noted that the flavonoids in milk thistle (the compounds generally considered to be ‘active’) have poor bioavailability. Instead, they examined a related compound and noted that it “provides significant liver protection and enhanced bioavailability over conventional silymarin.” This doesn’t exactly make a great case for Clear Head . . .

- Milk thistle for the treatment of liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. (2002)

- This review concluded: “We found no reduction in mortality, in improvements in histology at liver biopsy, or in biochemical markers of liver function among patients with chronic liver disease.” They noted the data were too limited to “support recommending this herbal compound for the treatment of liver disease.“

- Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases. (2007)

- This Cochrane review concluded: “Our results question the beneficial effects of milk thistle for patients with alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases and highlight the lack of high-quality evidence to support this intervention.”

- Milk thistle and its derivative compounds: a review of opportunities for treatment of liver disease. (2013)

- This was a review for veterinary applications in a veterinary journal that concluded: “Future study is justified to evaluate dose, kinetics, and treatment effects in domestic animals.”

- A review of Silybum marianum (milk thistle) as a treatment for alcoholic liver disease. (2005)

- This review’s conclusion is similar to my own conclusions: “while Silybum marianum and its derivatives appear to be safe and the available evidence on the mechanisms of action appears promising, there are currently insufficient data from well-conducted clinical trials to recommend their use in patients with alcoholic liver disease.”

- Milk Thistle (Silybum Marianum) : A Review. (2011).

- This is another narrative review published in a low-quality journal. Even so, it concludes: “available evidence is not sufficient to suggest whether milk thistle may be more effective for some liver diseases than others or if effectiveness might be related to duration of therapy or chonicity and severity of liver disease.” In other words, there is no high-quality evidence on the topic.

Search query: “allintitle: milk thistle clinical”

- Clinical assessment of CYP2D6‐mediated herb–drug interactions in humans: Effects of milk thistle, black cohosh, goldenseal, kava kava, St. John’s wort, and Echinacea. (2008)

- This study examined in vivo effects of milk thistle supplementation and found that – contrary to in vitro studies – it is not a potent modulator of CYP2D6 activity. On the one hand, this means that concomitant supplementation milk thistle with CYP2D6 substrate drugs is unlikely to result in interactions, but, on the other hand, this demonstrated the failure of milk thistle to impact a biochemical pathway that may have been expected from basic science research and animal studies.

- Milk Thistle for Alcoholic and/or Hepatitis B or C Liver Diseases—A Systematic Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group Review with Meta-Analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials. (2005)

- This Cochrane review concluded that milk thistle “does not seem to significantly influence the course of patients with alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C liver diseases.“

- Assessing the Clinical Significance of Botanical Supplementation on Human Cytochrome P450 3A Activity: Comparison of a Milk Thistle and Black Cohosh Product to Rifampin and Clarithromycin. (2013)

- Conclusion: “Milk thistle and black cohosh appear to have no clinically relevant effect on CYP3A activity in vivo.”

- Milk Thistle: Effects on Liver Disease and Cirrhosis and Clinical Adverse Effects: Summary. (2000)

- This review concluded: “clinical efficacy of milk thistle is not clearly established. Interpretation of the evidence is hampered by poor study methods and/or poor quality of reporting in publications.” In terms of side-effects, “available evidence does suggest that milk thistle is associated with few, and generally minor, adverse effects.”

- The Clinical Utility of Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum) in Cirrhosis of the Liver. (2002)

- The review concluded: “major flaws in many of the studies make it difficult to draw solid conclusions.“

Search query: “allintitle: silymarin clinical”

- Hepatoprotective Herbal Drug, Silymarin From Experimental Pharmacology to Clinical Medicine. (2007)

- Though the article is referenced as being published in the Indian Journal of Medical Research (a rather low-quality journal), this narrative review is hosted on the site RedOrbit, which appears to be news, but is merely a promotional outlet. This article is simply not even worth addressing.

- Silymarin: A Review of its Clinical Properties in the Management of Hepatic Disorders. (2001)

- Regarding the properties of silymarin, the study concludes: “studies evaluating relevant health outcomes associated with these properties are lacking.”

- The efficacy of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. (silymarin) in the treatment of type II diabetes: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, clinical trial. (2006)

- It’s nice to see an RCT, but the paper was published in a low quality journal and suffers from methodological issues. I won’t perform a full analysis as the paper concerns diabetes.

- An Updated Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis for the Clinical Evidence of Silymarin. (2008)

- This is another low quality journal and review. How shoddy is this journal? Well when I opened the link there was a fucking animated skeleton telling me to participate in a survey to win a prize. Alternative medicine journals: always good for a laugh. The earlier referenced Cochrane review performed a review on the same subject only a year earlier and with greater rigor. Refer to it.

- Combined therapy of silymarin and desferrioxamine in patients with β‐thalassemia major: a randomized double‐blind clinical trial. (2009)

- This was a low quality RCT examining silymarin supplementation among β‐thalassemia patients. The study isn’t relevant to this article, but for curious readers, I recommend taking a look at Tables II and III for some glaring issues in this study.

- Silymarin in treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized clinical trial. (2014).

- Another RCT published in a very low quality journal. Again, glaring issues and not relevant to hangovers.

- Combined effects of silymarin and methylsulfonylmethane in the management of rosacea: clinical and instrumental evaluation. (2008)

- This paper concerns a topical treatment of a skin condition . . .

- The Efficacy of Silymarin in Decreasing Transaminase Activities in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. (2008)

- Another low quality journal, however, they do report some promising initial results for NAFLD markers, although clinical outcomes were not evaluated. Again, this is not a study on hangovers.

- Effects of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. (silymarin) extract supplementation on antioxidant status and hs-CRP in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. (2015)

- Low quality journal, some methodological issues, and concerning diabetes again. As an aside, the Editor in Chief of the journal (Phytomedicine) is the head of research & development at Swedish Herbal Institute, a company which essentially uses bad science to market dubious products. Sound familiar?

- The Safety and Efficacy of a Silymarin and Selenium Combination in Men After Radical Prostatectomy – A Six Month Placebo-Controlled Double-Blind Clinical Trial. (2010)

- Why? Why does this exist? Regardless, the study is not relevant and I haven’t the time to describe every methodological issue. Refer to Table 3 to see where the authors went fishing for significance with dynamite.

Search query: “allintitle: silymarin safety”

- A randomized controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy of silymarin on symptoms, signs and biomarkers of acute hepatitis. (2009)

- Another masterpiece published in Phytomedicine. I’ll just leave this portion of the conclusion here: “our results suggest that standard recommended doses of silymarin are safe and may be potentially effective in improving symptoms of acute clinical hepatitis despite lack of a detectable effect on biomarkers of the underlying hepatocellular inflammatory process.” The authors also concluded that “patients receiving silymarin had earlier improvement in subjective and clinical markers of biliary excretion,” which can be decoded from science-speak to “we didn’t find the result we were looking for, so here’s an artefact of our poor methodology to help get this published.“

- Maca (Lepidium meyenii) and yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius) in combination with silymarin as food supplements: In vivo safety assessment. (2008)

- The study was not specific to silymarin and – quite frankly – does not tell us much of anything.

- Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of Silymarin in β-Thalassemia Patients: A Review. (2015)

- This is not a systematic review, not related to the topic at hand, and calls for more research on the topic.

- The effect and safety of combination of silymarin and leuprorelin for the treatment of endometriosis. (2011)

- I’m not even going to address this . . . click the link if you dare.

- Potentiality and safety assessment of combination therapy with silymarin and celecoxib in osteoarthritis of rat model. (2013).

- What aspect of rats with osteoarthritis is relevant to humans experiencing a hangover?

- Phase I Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics (PK) of Silymarin (SM) Following Chronic Dosing in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C (HCV). (2008)

- As in the title, the study does not address efficacy of the treatment.

Search query: “allintitle: silymarin review”

- Silymarin treatment of viral hepatitis: a systematic review. (2005)

- Conclusion: “There is no evidence that silymarin affects viral load or improves liver histology in hepatitis B or C. No studies were found that investigated the use of silymarin concomitantly with interferon, nucleoside analogues, or other conventional treatments for hepatitis B or C. In conclusion, silymarin compounds likely decrease serum transaminases in patients with chronic viral hepatitis, but do not appear to affect viral load or liver histology.”

- Silymarin: A review of pharmacological aspects and bioavailability enhancement approaches. (2007)

- The review noted that silymarin: “is orally absorbed but has very poor bioavailability due to its poor water solubility.”

- An Updated Systematic Review of the Pharmacology of Silymarin. (2007)

- “Conclusions: Data presented here do not solve the question about the complex mechanism(s) of action of the medicinal herbal drug silymarin.“

- Silymarin- A review on the Pharmacodynamics and Bioavailability Enhancement Approaches. (2010)

- Again: “the main drawback of silymarin is its poor solubility therefore different approaches are been taken to enhance the solubility in turn the bioavailability of the drug.”

- Potential Renoprotective Effects of Silymarin Against Nephrotoxic Drugs: A Review of Literature. (2012)

- “Whether the protective administration of silymarin could be an effective clinical pharmacological strategy to prevent DIN is a question that remains to be answered in clinical trials.“

- Silymarin and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic, comprehensive, and critical review. (2015)

- This is a poorly done review that even fails in some areas of basic science, and relies heavily on studies in rats to draw conclusions. They conclude, as they should: “well-designed clinical studies are urgently needed to evaluate the full potential of these natural agents to effectively treat or reduce the risk for liver cancer.”

- A Review on Hepatoprotective Activity of Silymarin. (2011)

- Perhaps the lowest quality journal yet. The ‘study’ is worth a read if you’re looking for an example of how to avoid thinking critically and how not to perform a literature review.

- Silymarin: a comprehensive review. (2009)

- Basically the same as above.